By Doug

I don't like to use my compass for a bunch of reasons. It tells me lies, like where not to go in a persistent shift. It keeps me perfectly in phase as I sail right past the mark. And it makes me sail with my head in the boat ensuring that I miss everything that's going on outside the boat. It's no wonder that some of the best Laser sailors in the world don't even own a compass.

But in some cases, a compass can be invaluable. At the recent Austin YC Centerboad Regatta, mine decided to work really well. The fleet was good and had lots of speed, but picking the shifts was everything. Many of these articles start with Pam asking, "How did you do that?" So, here's how I used my compass to win 7 of the 8 races.

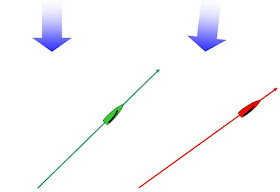

I use an aging Silva compass because it's easy to read and the numbers are simple - there is very little math required and it has arrows on the side that tell you which way is lifted. I start at the committee boat close hauled and sail upwind getting a reading. This is repeated until the range of shifts are clear. In this case on Lake Travis, the wind went right to 9.0 and then left to 11.5, with 10.5 being where it stayed most of the time. With a Silva compass, each 1.0 is worth almost 20 degrees, so the wind was shifting almost 50 degrees. That's is a lot, even for lake sailing!

|

| Starboard tack, neutral - this is the number everything else is based on. |

|

| Starboard tack, numbers are down (see arrow), I'm on a lift... good. |

|

| Starboard tack, numbers are up, I'm on a knock... think about tacking. |

Here are the same readings on port tack. For some reason, port tack numbers on this compass are 10 below starboard. For example, 0.5 on port tack is 10.5 on starboard.

|

| Port tack, neutral - this is the number everything else is based on. |

|

| Port tack, numbers are up (see arrow), I'm on a lift.... good. |

|

| Port tack, numbers are down, I'm on a knock... think about tacking. |

When I spent time with Frank Bethwaite, he taught me about how to measure the timing between these shifts, how this time would decrease when going upwind, and how they would increase going downwind. This works for open water sailing where the shifts can be steady, but I have trouble making this work on lakes where the shifts are more random. Just keep this in mind if you're in open water.

So, come along for a ride in a typical race at AYC this past weekend. If the wind is to the left 11.0 or more (starboard, knocked), we'll start near the pin (favored end) on a knock and try to tack ASAP. If the wind is to the right, 10.0 or less (starboard, lifted), we'll start at the committee boat (favored end) on a lift so that we can tack when needed. Most of the time, the compass is 10.5 where the direction is neutral, so we still start at the boat and keep our options open.

With 2 minutes to go, we're close-hauled near the committee boat to get a reading of the wind, also noting if there are any velocity changes coming down the lake that would override our preference of starting on a lift. Here's our reading.

|

| Big knock, pin favored, will need to tack ASAP. |

We get ready to head down the line and check again with 1 minute to go. It's gone to 10.5 neutral and may continue to shift to the right.

|

| Change of plan, head for the committee boat end. |

We start at the boat and go left with the fleet below us. A slight knock means we may have to tack while a lift is good. We keep going waiting for things to develop. I do not have a good feeling for what is next, so we stay with the fleet until our first knock.

|

| Want to tack ASAP. |

But there's a dark patch up ahead so we sail through the knock as others tack and pass behind us. The increased pressure brings a bigger knock, which is normal on small lakes. We're ready for the puff and tack right away, and now enjoy a larger lift than the boats below us.

|

| Life is good - we keep lifting. |

With the wind shifting back and forth we can expect a knock, plus most of the fleet is below us going right. It's good percentage sailing to stay on port as long as possible to consolidate.

Sure enough, after a few minutes, we start to get the expected knock.

|

| We're sailing into a knock. |

Most people tack on this knock and pass behind us. But the compass tells us that we're only neutral, just half way through the knock (remember we tacked onto a lift). Another thing that Frank taught me is to not tack here because we want to be inside the next shift, so we hold on for the knock to fully develop.

|

| We're fully into the knock. |

Now we tack and are again inside the right shift, like being on the inside of a circle. The speed of the fleet is about the same but is beginning to spread out because of the extra distance that some are sailing.

As we get close to the mark, our compass goes from being our friend to our enemy. We do not want to be sailing in a circle with the mark at the center because there's a good chance that the next knock will not come in time (the last shift is always persistent), and we'll lose many places if we tack and come in on a huge knock. So we ignore our compass and sail on the knock so that when we tack the lift takes us up to the mark while others sail a big old circle around it.

Here's what our first leg has looked like.

So, the compass is our overall strategy - like a coach making real-time suggestions, but they're only suggestions to think about. There are always other things to consider, like where's the next puff likely to come from? Where's the mark? How far away is the mark? What's my nearest competitor doing? What's the fleet doing? And in Austin, where's Fred (he loves to bang the corners).

The really cool thing that I love about lake sailing is that all of these factors are constantly changing, and a compass helps put them into perspective.

Glance at it, consider it, and learn from it. But remember to keep your head out of the boat or else your compass will just be a big distraction.

.JPG)